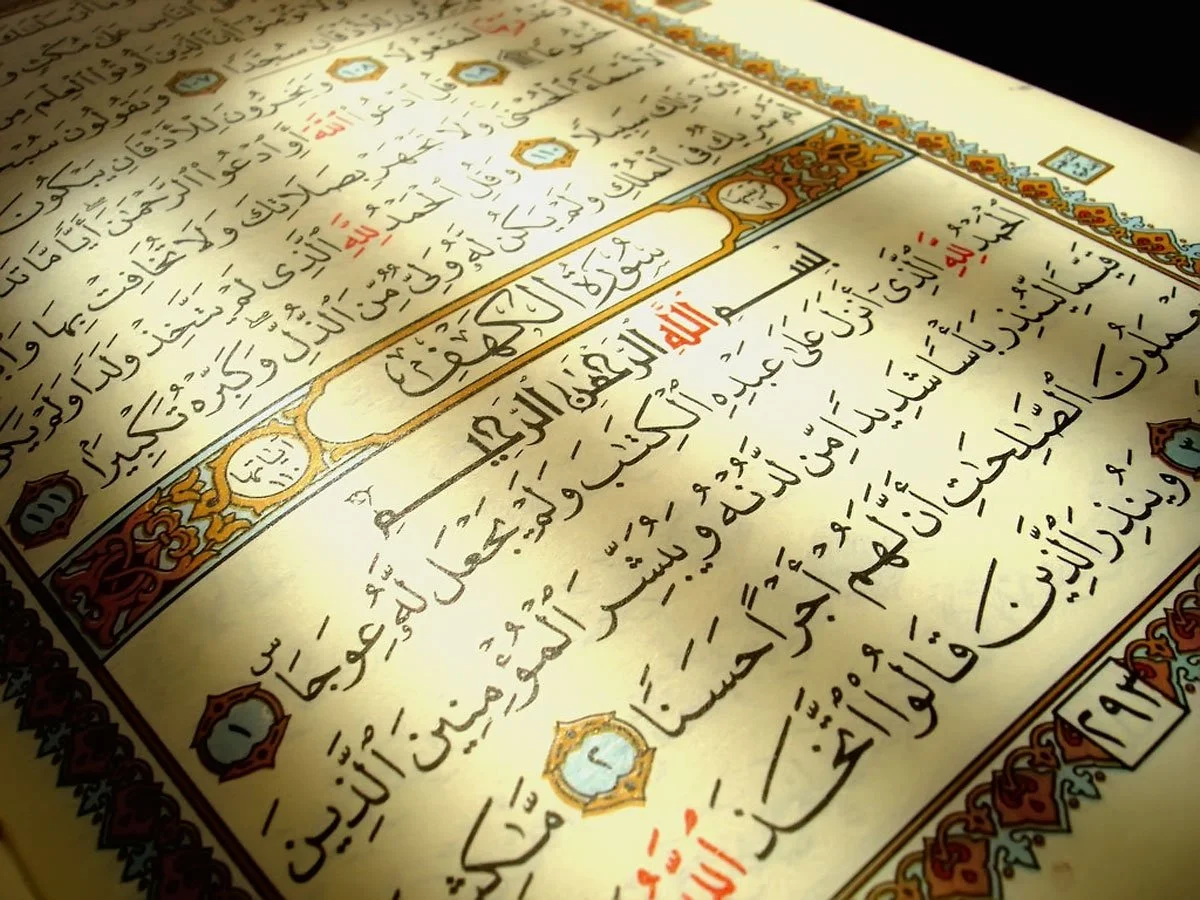

“THIS BOOK…

ABOUT WHICH THERE CAN BE NO DOUBT”

(The Holy Qur’an — Chapter 2, Verse 2)

This is a brief note on the purpose and perspective of this section.

On this page, I share a series of essays on the Qur’an—focused readings of specific verses, passages, and narratives that I believe reward careful and sustained attention.

Given the vast amount of material already written about the Qur’an, a reasonable question arises: why add one more voice?My reasons are straightforward.

Why Another Set Of Essays

First, I have come to believe that the Qur’an is the most unique, profound, and beautiful book ever sent to humanity. This is, of course, a strong claim, and it deserves to stand or fall on evidence rather than assertion. Yet much of the traditional argumentation offered in support of this view either relies on medieval intellectual frameworks unfamiliar to modern readers, or requires specialized training—such as deep immersion in ancient Arabic poetry—simply to evaluate the argument.

If the Qur’an is truly timeless, however, its distinctive qualities should not depend on historical distance or scholarly gatekeeping. Its coherence, literary precision, conceptual depth, and internal consistency should remain visible to attentive readers in any age—including those shaped by modern analytical and scientific ways of thinking. One aim of these essays is to explore whether, and in what ways, this is true.

On Misreading The Qur’an

Second, the Qur’an is frequently misunderstood, not only by its critics but sometimes by its readers as well. This is not accidental. Precisely because the Qur’an is such a unique book—unlike any other in its structure, mode of argument, and way of conveying meaning—it is often approached with expectations that simply do not apply to it. Readers bring assumptions shaped by linear narratives, systematic theology, or philosophical treatises, and when the Qur’an does not conform to these frameworks, premature and often mistaken conclusions follow. Many of the issues addressed in these essays arise from this mismatch rather than from a careful engagement with the text on its own terms.

A Note On Perspective

Third, and more personally, I find the Qur’an to be an extraordinarily beautiful work—though not in a way that reveals itself quickly. Its beauty emerges through slow reading: attention to word choice, sensitivity to structure, and patience with how meaning unfolds across verses and chapters. This way of reading reflects a long engagement with the Qur’an that began in my teenage years and continued alongside a modern academic education and research career spanning several decades, primarily in the natural sciences, economics, and the social sciences.

As often happens over a long intellectual journey, many views I once held with confidence gradually changed, while others I had previously dismissed came to appear in a very different light. Through all of these shifts, however, my assessment of the Qur’an moved steadily in one direction: toward the conclusion stated at the outset—that it is a uniquely profound and enduring book.

The articles that follow are an attempt to show why.

Of the 114 Chapters of the Qur’an six of them are named after animals: the cow, the cattle, the bee, the spider, the ant, and the elephant. In these chapters, the animal named in the title is typically mentioned only briefly but in a way that carries a profound meaning.

The chapter of “The Spider” is one of these. The word spider occurs twice in verse 29:41 of this Chapter and nowhere else in the Qur’ān.

“The parable of those who take protectors other than Allah is that of the spider, who builds (to itself) a house (bayt); but truly the flimsiest of houses is the spider's house — if they but knew.” (Q29:41)

At first glance, the verse appears to make a straightforward comparison: just as a spider's web is fragile and weak, so too is the protection offered by those who seek guardians other than God. Yet beneath this surface reading lies a masterpiece of divine rhetoric that rewards deeper contemplation with profound insights.

While the average reader would be satisfied with the surface reading based on the apparent weakness of a spider’s web, in reality, the weakness is largely illusory because the spider web is also exceedingly thin and light.

Indeed, spider silk is one of nature’s most remarkable materials: it is stronger than high-grade alloy steel and tougher than kevlar, and it can stretch several times its length without breaking. So, if the verse is describing physical weakness, it seems to contradict material reality.

In truth, this “contradiction” serves as an interpretative trigger, compelling the reader to look beyond the physical properties of spider silk to discover what kind of weakness is actually being described.

I was pondering a passage in the Qur’ān about the moon — “al-Qamar” in Arabic — and wondered if the word had any other meanings or metaphorical usage. When I checked the Quranic Quranic Arabic Corpus, I saw that it lists a total of 27 occurrences of al-Qamar in the Qur’an.

“Twenty-seven?” I thought to myself. “That’s only a few days shorter than the length of the lunar month.”

Yes, miracles… some of which are so profound and comprehensive that it would take volumes to show them in all their glory; others that are “bite-size,” so to speak — delightful wonders that can potentially be noticed by anyone who reads the Qur’an with an open mind and a sincere heart.

I had this nagging feeling — because the Qur’an never has a near miss. Anytime it dangles a “marvel” or a “sign” in front of us that looks close-but-not-exact, you can be sure that there is a twist that we missed. And when we finally figure it out, we realize that the connection is even more perfect and beautiful than we had initially suspected.

As I was pondering these, I remembered…